Judy Middleton (2002 revised 2023)

|

| copyright © J.Middleton This marvellous old postcard gives you some idea of the appearance of Waterhouse’s Hove Town Hall although in reality the bricks were a deeper shade of red. |

Brunswick Street West

The first Town Hall at Hove stood in Brunswick Street West. It is rather a grandiose building for a narrow street and it is difficult to appreciate the classic proportions of its façade from such a restricted angle. It is also interesting to note that the building was not intended to be a Town Hall at first. It was erected out of necessity when Brighton received its Charter of Incorporation in 1854. The outcome of this for neighbouring Hove was that miscreants arrested for an offence committed within the Brunswick Town area could no longer be hauled before the Brighton Magistrates, as had been the custom. The Brunswick Square Commissioners were obliged to erect their own Court House, which also included accommodation for the police and the necessary cells. The building cost £3,000 and was finished by 1856.

Meanwhile, the town of Hove was growing rapidly and legal jurisdiction soon passed from the Brunswick Square Commissioners to the Hove Commissioners. Thus in 1873 the Hove Commissioners took over the building in Brunswick Street West, which became Hove Town Hall.

Although the building looked large enough for the purpose, it soon became apparent that there was a desperate shortage of space. George Breach, Chief Superintendent of Hove Police, was the first person to feel the winds of change. He had seen service locally since 1836 and was living ‘over the shop’, as it were. In 1876 he was asked to find quarters elsewhere to free up space for more offices. Then there was the feeling that a Town Hall should be more centrally placed to take account of the increase in population in the west of the town and not squeezed into an inadequate space at the eastern extremity. A new site was identified and a grandiose Town Hall was constructed. The old Town Hall was sold off in May 1884. The supreme irony is of course that while the magnificent Town Hall was devastated by fire in 1966 and subsequently demolished, the old Brunswick building still stands to this day.

Waterhouse’s Hove Town Hall

In June 1877 the Hove Commissioners purchased a site between Norton Road and Tisbury Road for £6,000 from the Stanford Estate; George Corney, Mrs Ellen Bennett-Stanford and the Hove Commissioners signed the document. The relevant committee received seventeen tenders to build the Town Hall. Surprisingly enough, John Thomas Chappell provided the lowest tender at £30,800 and was chosen to undertake the task. He was a well-known local builder who was responsible for many fine houses at Hove but perhaps this commission was at the start of his career or he wanted the prestige of building the Town Hall. It is a fact that later on, he was considered a somewhat expensive builder and for this reason was not selected to erect All Saints Church in The Drive. On 29 October 1879 the Hove Commissioners and J.T. Chappell signed an agreement to erect a Town Hall and according to Henry Porter it took two years and seven months to construct.

Alfred Waterhouse (1830-1905) was the architect chosen to design Hove Town Hall. It has been remarked that he was the High Victorian Architect, par excellence, and it was certainly the case that he became the busiest and richest of them all. The Hove Commissioners might have been influenced by Waterhouse’s design for Manchester Town Hall, recently opened in 1877. It had been a long haul for Waterhouse because the Manchester competition took place in 1866 and there were no less than 130 entries. Waterhouse’s design was the final choice not just because it was the cheapest option but also because it provided more window light and natural ventilation. Not everyone at Hove was enthusiastic about the choice and some thought Hove was getting rather above itself; indeed the Chairman of the Hove Commissioners commented that engaging such an eminent architect was like ‘applying a steam hammer to crack a nut’.

Some other famous Waterhouse designs include the Natural History Museum at South Kensington, University College Hospital, Manchester Assize Court, the south front of Balliol College, Oxford, Girton College, Cambridge, and, near to home, the Hotel Metropole Brighton and the Prudential Buildings, both at Brighton.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton Manchester Town Hall / Brackenbury Buildings, Oxford / Hotel Metropole. |

Hove Town Hall was built in the Renaissance style in red brick manufactured at the Keymer, Sussex works. In the 1880s it was stated the ‘beautiful, warm, red colour … has found many admirers’. The building had Portland stone facings and terracotta dressings. All the windows had mullions, transoms and crisped, tracery heads. Inside Beer stone was used because it was easier to chisel.

The Great Hall measured 90 feet x 60 feet and there were balconies on the east, south and west sides. The windows were glazed with pretty, geometrical-patterned coloured glass.

The Reception Room measured 22 feet x 18 feet. The tower was originally intended to be 110 feet high but it was increased to 120 feet. The west wing was home to the Town Clerk’s office, the Rate Collector’s Office and the Police Station.

Meanwhile, Hove Commissioners were obliged to take out a loan for £35,000 with interest at 4 ½ % and repayable within thirty years. James Warnes Howlett laid the foundation stone (called the Memorial Stone) on 22 May 1880 in the presence of the Bishop of Chichester, clergy and ministers. It was also Mr Howlett who formally opened Hove Town Hall on 13 December 1882. It had been hoped that the Prince of Wales would officiate at the opening ceremony but he had too many other engagements.

All the same, the splendid inaugural banquet was fit for a Prince. Leaving aside such delights as soups, fish, entremets, and desserts, the main part of the menu consisted of turbot with lobster sauce, salmon with matelotte sauce, oyster cutlets, lark and kidney puddings, fricassee of turkey, York hams, haunches of venison and mutton, pheasants and wild duck together with the finest champagne including Perrier Jouet’s First Quality, and Moet’s First Quality.

This was by no means an isolated example of a splendid repast being dished up at the Town Hall. For instance, there was the inaugural banquet held on 14 May 1891 for George Woodruff, Chairman of the Hove Commissioners. The menu was as follows: turtle soup (both clear and thick) salmon, turbot, stewed eels, roast lamb, saddle of mutton, York ham, roast ducklings, conserve of apricots and charlotte russe. The food was eased on its way by milk punch, Amontillado, Rudesheimer vintage 1868, Heidsieck 1884 dry Monopole, Irroy magnums 1884, Chateau Margaux, old port and Irish whiskey, soda, seltzer and Appolinaris – the latter two being mineral waters.

The patriotic people of Hove would have liked a flagstaff at the Town Hall but in March 1882 H.H. Scott, surveyor, reported he had been unable to find a suitable place. Then a letter arrived from Alfred Waterhouse saying ‘he looked on the addition of a flagstaff with some reprehension’ and the matter was quietly dropped. However, in 1900 an anonymous benefactor paid all the expenses incurred in erecting a flagstaff at the Town Hall.

In 1893 the Commissioners resolved to light Hove Town Hall with electric light and fifteen tenders were delivered to the surveyor H.H. Scott who was advised by consulting electrician Frank King. But the Local Government Board refused to allow Hove to borrow the sum of £1,600, the cost of installing electricity, unless the Commissioners gave an undertaking that the loan would be repaid within ten years. The assurance was given and on 12 October 1893 Messrs Crompton & Co signed the contract with the work being carried out the following year.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton The photographer was looking westwards when he took this very clear view. The width of the road seems impossibly wide because there is so little traffic. |

The Town Hall Bells

|

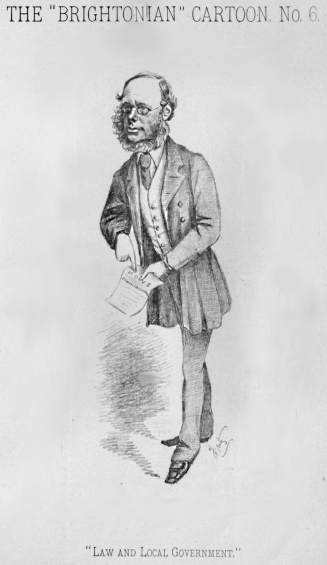

| copyright © Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove James Warnes Howlett (1828-1911) |

In 1882 a carillon of twelve bells was installed in the tower of the Town Hall; the hour bell weighed 36 cwt, was tuned to C natural and inscribed with the name of James Warnes Howlett. The second largest bell was inscribed with the name of G. Marsh because he took an active part in obtaining subscriptions towards the cost of the clock and carillons.

James Warnes Howlett (1828-1911) moved to Brighton in 1857, joining a legal firm that later became Attree, Clarke and Howlett. He lived at Brunswick Place, Hove and was one of the original Hove Commissioners. He earned the title of the ‘Father of Hove’ because he fought strenuously to keep Hove independent of Brighton when Brighton tried to annexe the town in the 1870s. In 1876 Howlett declared ‘the prosperity and good government of Hove would suffer severely under union with Brighton.’ (There are many ardent Hoveites today who feel his opinion was prophetic). A popular local jingle from the 1870s went as follows:

Howlett and Hove Names

almost synonymous

Since Howlett’s sharp move

Made Hove autonomous.

It was in view of his stalwart work on behalf of Hove that meant Howlett was the natural choice to lay the foundation stone on 22 May 1880 and to formally open the Town Hall on 13 December 1882. Howlett was described as a tall, gaunt figure with one eye but he kept a fine cellar and even as an old man enjoyed choosing from some fifty or sixty different wines. Howlett donated £105 towards a memorial to Edward VII (the highest individual contribution) that later resulted in the erection of the Peace Statue.

The twelve bells weighed a massive nine tons. Messrs Gillett & Bland supplied the bells as well as the clock for the sum of £1,576-10s. In Victorian and Edwardian times the carillon performed every third hour during the day and the following airs resounded through Hove.

Barrel Number One

Sunday - Hanover

Monday - Home Sweet Home

Tuesday - The Blue Bells of Scotland

Wednesday - The Harp That Once in Tara’s Hall

Thursday - March of the Men of Harlech

Friday - The Anchor is Weighed

Saturday - Rule Britannia

Barrel Number Two

Sunday - Sicilian Mariners’ Hymn

Monday - God Bless the Prince of Wales

Tuesday - There’s Nae Luck Aboot the House

Wednesday - The Last Rose of Summer

Thursday - Auld Lang Syne

Friday - Tom Bowling

Saturday - God Save the Queen/King

A somewhat sad anecdote appeared in the Brighton Herald (24 September 1910);

Reference has often been made to the irony of the Hove Town Hall carillons. Another instance occurred last Monday. The magistrates were engaged with a particularly sordid and painful case of parental neglect, when the bells over their heads went sardonically through the strains of Home Sweet Home.

There was an ivory keyboard attached to the carillon apparatus that enabled different tunes to be played on the bells on special occasions. But it was a challenge for a professional organist because it required a different technique and of course there was only a range of twelve notes to strike the twelve bells. The operator had to strike the key sharply with the thumb of a clenched fist.

On 16 July 1893 Mr Crapps played the carillon bells on the occasion of the royal wedding when Prince George, Duke of York (later King George V) married Princess Mary of Teck.

Later on S.H. Baker held the unusual and honorary appointment of Borough Organist of Hove and he played the carillon bells on three historic occasions. They were Armistice Day 1918, Coronation Day 12 May 1937 and V.E. Day 1945. Apparently the keyboard was mislaid between the two first events but fortunately it was discovered and fitted up in time. According to E.V. Lucas the Admiralty stopped the carillons being played during the First World War on the grounds the sound might act as a guide to submarines or aircraft. On VJ Day 1946 the bells started to ring out at 8a.m. with There’s Always Be An England.

In January 1916 it was suggested that the times the carillons played should be altered. Up until then the carillons had been merrily ringing out every three hours from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. The new times restricted their use to four times daily instead. On occasions the carillons could be heard while a concert took place inside the Town Hall, which was a cause of annoyance to some of the audience. By the time the 1950s arrived the carillons only played once a day at 1 p.m.

In 1921 an inspection revealed that sea air had corroded the wires connected to the bells. Messrs Gillett & Johnston recommended phosphor bronze connections should be substituted at a cost of £54. But Hove Council chose the cheaper option of galvanized iron wire with extra heavy ‘S’ hook joints for £48-10s.

Town Hall Clock

Messrs Gillett & Bland supplied the clock at the same time as the carillons at a cost of £1,576-10s. Messrs Salviati, Burke and Company supplied the mosaic clock dials for £180. In December 1892 the surveyor was instructed to fix small gong bells to the winding gear of the clock and carillon to prevent over-winding.

In 1893 when the Hove Commissioners were thinking about installing electricity in the Town Hall, Frank King, consulting electrician, advised against illuminating the clock tower and clock faces because of the ‘amount of experiment in consequence of the novelty of the work’. The surveyor H.H. Scott added the information that owing to the construction of the dial plates, the clock could not be illuminated from the inside.

Eighteen years later technology had improved enough for the illumination to become possible and in March 1911 it was reported that James Warnes Howlett would pay the cost of £300 to have it installed. Alfred Waterhouse’s son drew up the plans and Messrs Gillett & Johnson undertook the work.

Mr G.F. Matthew of the Indian Service (retired) in a letter dated 21 December 1906, complained about the ‘sonorous and penetrating’ chimes of the Town Hall clock; he found the midnight chimes particularly annoying. He asked that the striking mechanism should be stopped between the hours of midnight and 6 a.m. Moreover, sixty-two residents of neighbouring streets added their signatures to the letter. When the committee learned that it would cost £25 to alter the mechanism they decided, after some discussion, that they could not recommend the council to stop the striking at night.

Town Hall Organ

The original organ was a relatively simple instrument. In February 1896 the Town Hall Committee reported they had made enquiries and it would cost from £1,600 to £1,700 to complete the organ in a suitable manner.

By September 1896 the Local Government Board had sanctioned Hove Council’s application to borrow £1,700 to be repaid within a period not exceeding thirty years. In November 1896 Henry Willis of Rotunda Works, Camden Road, London, signed a contract to complete the organ. However, his specification came to more than the original estimate because he stated the work, including mechanical blowing, would cost £1,820.

Henry Willis (1821-1901) was a famous organ builder and he had constructed the organ in the Albert Hall in 1871. He also built the organ in Windsor Castle and others for various halls and cathedrals. In 1885 Henry Willis received a gold medal for his organ building because of the ‘excellence of tone, ingenuity of design and perfection of execution’. The Hove Town Hall had four complete manuals. Henry Willis recommended the pitch for the organ should be the French Diaspon Normal. It is not clear whether or not this was done and altered later but it is a fact the Council Minutes for June 1915 record the pitch should be altered to French Diaspon Normal.

There was also the matter of the water supply to sort out because the great organ was to be blown by three Ross water engines. To operate efficiently these engines needed a constant minimum pressure of 50lbs per square inch whereas in March 1897 the ordinary pressure in the water main at the Town Hall was 35lbs per square inch. An additional connection to the water main by which a minimum pressure of 64lbs could be maintained at all times solved the problem.

On 30 June 1897 Mr H.F. Balfour ceremoniously inaugurated the magnificent newly completed organ. He gave two recitals that day, one starting at 3 p.m. and the other at 8 p.m. He began his performance with Bach’s Tocatta and Fugue in C Major and finished with a stirring rendition of Rossini’s William Tell.

The organ was insured for the sum of £2,000 and ordinary residents of Hove were allowed to use it, provided they could produce a certificate from a qualified organist that they were competent to play. For the serious musician, it was a bargain to be able to play such a fine instrument for 4/- an hour (if you were a Hove resident) or 5/- (if you came from elsewhere). In September 1897 it was decided to install an electric light in the organ loft at a cost of 3/-.

In December 1897 the surveyor H.H. Scott reported that there were sixty-two exposed pipes in the organ front, and they varied in length from 3 feet 6 inches to 13 feet 5 inches, and in diameter from 2 inches to 6 ½ inches. There was a considerable amount of ornamental woodwork in the organ case but the councillors must have thought the pipes looked somewhat bare because they instructed Mr Scott to put some simple decoration on the pipes at a cost of around £40.

In November 1898 the firm of Henry Willis & Son offered Hove Council a special deal for tuning the organ at a cost of £20 a year. They agreed to visit the organ for tuning purposes six times a year, provided that the experienced tuner and his assistants made four of these visits during the course of their ordinary rounds. Otherwise, the cost of hiring two men (including their time, railway, railway, bus or cab fares and hotel expenses) would amount to three guineas for the first day, £4-14-6d for two days and £5-16-6d for a three-day visit. Hove Council sensibly decided to opt for the £20 annual fee.

In the autumn of 1898 Mr Butcher gave four free organ recitals and programmes were not allowed to cost more than one penny.

In May 1928 there were several applications for the post of Honorary Borough Organist. Samuel H. Baker of 14 Wilbury Avenue was chosen for the post. He had been organist and choirmaster at St Mary’s Church, Brighton, and he was formerly deputy organist of Chichester Cathedral. Mr Baker was much in demand for official and semi-official occasions.

Although the organ had once been very popular, by the 1950s it was virtually a forgotten masterpiece. There had not been a single booking for an organ recital during the course of twenty-nine years. When discussing its future, one councillor was of the opinion that ‘organ recitals are as dead as a dodo’. Eventually it was decided to sell the Willis organ to Haberdashers’ Aske’s School at Elstree for the bargain price of £1,500.

Many music buffs were upset at Hove losing such a fine instrument but at least they had the consolation of later knowing that had it remained at Hove, it would have been destroyed with the rest of the Grand Hall in the fire of 1966.

Sir Charles Aubrey Smith

In May 1889 the Hove Commissioners granted a theatrical licence to the Great Hall and Banqueting Room. Orchestral concerts had already taken place on the stage and in 1887 the Green Room Club for aspiring actors was formed. It seemed the existing stage was not large enough and in 1895 Parsons & Sons were commissioned to erect a moveable timber stage to place in front of the existing platform for the sum of £57-15s.

It is interesting to note that Sir Charles Aubrey Smith (1863-1948) and his two sisters were keen members of the Green Room Club and rehearsals took place at 56 Norton Road. Their father was a surgeon who lived for many years at 2 Medina Villas but later the family moved to 19 Albany Villas, which was where a commemorative plaque was unveiled in May 1987. Aubrey Smith made his acting debut at Hove Town Hall on 8 November 1888 as Mr McAlister in a production of Ours. His last stage appearance at Hove was also at Hove Town Hall on 17 February 1894. He made his London debut on 9 March 1895 at the Garrick Theatre where he portrayed the clergyman in The Notorious Mrs Ebbsmith.

In 1915 Aubey Smith embarked on his film career; he played the part of Wellington in Queen Victoria. Other notable films he appeared in were Lives of the Bengal Lancers (1935) with Gary Cooper, The Prisoner of Zenda (1937) with Ronald Colman, Madeleine Carroll and Douglas Fairbanks, The Four Feathers (1939) with Ralph Richardson and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1941) with a star-studded cast including Spencer Tracy, Ingrid Bergman and Lana Turner.

As well as being a famous thespian, Aubrey Smith was also a noted all-round sportsman, having gained his blue at Cambridge in 1882. He was a commanding figure with a height of over six feet and he was known as both a batsman and a bowler. From 1882 to 1886 he played cricket for the Sussex team from time to time and was captain from 1887 to 1889. In 1889 at the Sussex County Cricket Ground at Hove, he made 142 for Sussex against Hampshire and in 1890 he took seven wickets for sixteen runs against the MCC at Lords. He earned the nickname of ‘Round the Corner Smith’ because of his angled run-up to the crease. Sometimes he began from a deep mid-off position, while at other times he appeared from behind the umpire. Even the redoubtable W.G. Grace admitted ‘It is rather startling when he suddenly appears at the bowling crease.’ When Aubrey Smith moved to Hollywood and lived in a house in Mulholland Drive, Beverly Hills, he founded the Hollywood Cricket Team, which became a magnet for other British actors in Hollywood such as David Niven, Boris Karloff and Leslie Howard.

Aubrey Smith was also keen on football, playing for such famous teams as the Old Carthusians and Corinthians. In 1944 he was knighted and four years later he died at the age of 85 in Beverly Hills. His ashes were brought back to England and laid in the churchyard of St Leonard’s, Aldrington to join his sisters in the south-west corner.

In November 1898 approval was given for electric footlights to be placed on the stage at a cost of £21 and the orchestra was also to have the benefit of electric lights at a cost of £35. In 1901 it was decided to have electric top lights on the moveable stage instead of gas, which would also reduce the risk of fire. Thus three battens, each carrying twenty electric lamps, were installed at a cost of £50. Another modern innovation was the telephone, already installed in the basement. In September 1894 it was decided to provide a ‘silence box’ for it. Mr Miles was to provide and fix the same for £9-15s.

The Town Hall as a Cinema

While most people acknowledge that the first film show at Hove took place at the Town Hall, there is still some debate as to which film it was and the precise date. Some say the honour belongs to James Williamson who put on a cinematograph and Rontgen Rays show on 16 November 1897.

Others claim the first film shown was George Albert Smith’s Passenger Train made in 1897 and showing the arrival and departure of passengers at Hove Railway Station. (Incidentally, this film and other films made by local pioneers, can be viewed at a special gallery at Hove Museum. Hove is proud of its record in the forefront of the film industry, long before anyone had heard of Hollywood).

The Revd A.D. Spong of the Cliftonville Congregational Church had the bright idea that Passenger Train might amuse the young people of his church – he had already seen a preview. His son, A. Noel Spong, stood at the door collecting ticket money from excited youngsters.

In 1904 Hove Council produced a list of rules to be followed when a cinematograph lantern was in use and fire buckets and a damp blanket were to be placed close at hand. H.H. Scott, borough surveyor, also recommended that a compartment measuring at least six or seven feet should be provided to house the apparatus; it should be lined throughout with sheet iron and have a ventilated top. There was a natural concern about the possibility of fire because the celluloid film in use at the time was highly inflammable. In 1897 there had been the tragic case in Paris when a film show was given at a charity event and the celluloid film caught fire. The resulting blaze caused the death of 121 people.

The rules adopted in January 1904 were as follows;

The lantern must be constructed of metal or lined with metal and asbestos.

A metal shutter, in addition to the revolving disc shutter, must be provided between the source of light and the film, and kept closed except when the film is in motion for the purpose of projection.

If the film does not wind upon a reel or spool immediately after passing through the machine, a metal receptacle with a slot in the metal lid, must be provided for receiving it.

If electric lights are used, the installation must be in accordance with the usual rules, that is the choking coils and switch must be securely fixed on incombustible bases, preferably on a brick wall, and double pole safety fuses must be fitted.

If any oxy-hydrogen gas is used, storage must be in metal cylinders only.

The use of ether or other spirit saturator is not to be permitted under any circumstances.

In 1907 people in other parts of the Town Hall experienced fluctuations in the quality of the electric light whenever there was a film being shown. This was because the system was not designed for such high use and the demand sometimes rose to 60 amperes. In January 1908 Hove Council authorised alterations to the wiring; Page & Miles undertook the work at the modest cost of around £15.

It seems Hove Council were forward-thinking in their safety concerns because it was not until 1 January 1910 that the Cinematograph Act 1909 came into force. All the same some changes had to be made to comply with the new regulations; around £20 was spent on alterations to the operator’s enclosure and a further £24 was expended on providing electrically lit ‘Exit’ signs above each of the eight doors.

Film shows continued to be held at the Town Hall into the 1920s and a particular highlight in January 1920 was a film of the Prince of Wales’s overseas tour. G.H. Whitcomb played stirring music on the Town Hall organ to accompany the flickering film. At first of course Hove Town Hall was the only place where ordinary folk could see a film but soon dedicated cinemas were opened at Hove. The Empire Picture Theatre opened in Haddington Street in 1910, the Hove Electric Empire in George Street opened in 1911 and the Hove Cinema Theatre at 1 Western Road opened in 1912. These cinemas were of modest size and it was not until the early 1930s that large cinemas such as the Granada in Portland Road and the Odeon in Denmark Villas were in business.

Donations to the Town Hall

Gifts to the Town Hall were not unusual. In 1897 Charles H. Nevill of 3 Victoria Mansions offered a marble figure of a seated nymph called Sabrina executed by Holme Cardwell. The Town Hall committee accepted the offer and Sabrina became an adornment to the Mayor’s Parlour. Perhaps the mayor found the figure distracting; at any rate when the new Hove Library opened in 1909, Sabrina was moved there.

In April 1918 Sir George Donaldson (1845-1925) offered to present Hove with another marble statue. It was a 10-foot high replica of Canova’s fine sculpture called the Dancing Girl. Sir George ensured that the statue would be on public display and not tucked away somewhere; he insisted on choosing the spot himself.

Sir George Donaldson was an interesting character and he lived in some splendour at 1 Grand Avenue, Hove. He was an astute art connoisseur, dealer and collector and over the course of thirty years built up a unique range of musical instruments because he was a great music lover with the violin being his favourite instrument. In 1894 he presented this collection to the Royal College of Music. Amongst the treasures was an Italian 15th century upright spinet said to be the oldest keyboard instrument in existence, a pair of ivory and ebony mandolins belonging to the last Doge of Venice and a tortoiseshell guitar on which David Rizzio played before Mary, Queen of Scots. In 1900 he presented a collection of furniture to the Victoria and Albert Museum. Sir George was once heard to comment that Brighton and Hove had no equal in Europe and it was a mark of his respect for Hove that he offered the marble statue.

Hove councillors were moved to expend £50 to construct a special alcove opposite the main entrance to Hove Town Hall to accommodate the Dancing Girl. She stood on a circular pedestal, poised for movement, arms akimbo and wearing a loose, classical garment pinned at the shoulder. The profile of her head revealed her straight Greek nose and her hair was dressed in a ponytail style and adorned with a wreath of flowers. The original sculpture was created in 1805 for the Empress Josephine.

The statue presided over many interesting comings and goings during the course of years. But in January 1966 fire broke out at the Town Hall and although the Dancing Girl survived intact, she was blackened by smoke. Perhaps Hove councillors had more important things to worry about in the wake of the fire and having to find somewhere else for council meetings. At any rate nobody seemed to have much concern for Sir George’s bequest and Anthony Rea purchased her. She was cleaned up and stood for many years outside 3 Adelaide Crescent, adding a touch of elegance to her classic surroundings. Then in February 1995 thieves tried to steal the statue but only succeeded in snapping off her head and arms.

In 1907 Edwin Compton of 87 Goldstone Villas donated a painting by Jules Lessore. It was a view painted in 1882 of the King’s Road and it had cost £150. The painting in its gilt frame was 8-foot wide and hung in the Banqueting Room.

In November 1909 Councillor A.B.S. Fraser, Mayor of Hove, presented an etching by P. Laguillermie from the painting by Edwin Abbey The Coronation of King Edward VIII.

Lady Boyle, who was a member of the Sassoon family, bequeathed a portrait of Edward VII painted by a Mr Berthier. In July 1964 there was a row over a decision to hang this portrait in a corridor on the first floor. Councillor Edward Johnson objected and commented somewhat sourly that he did not like the idea of the council giving priority to ‘pictures of royal personages by artistic nonentities’. Perhaps he had forgotten that Edward VII made several visits to the Sassoons at their Hove home on the seafront and that at the time most residents felt honoured by the association.

The Hove Mayoral Chain and Badge

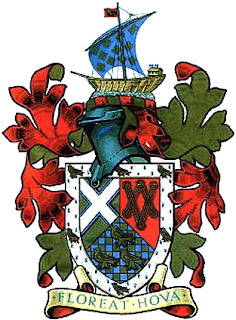

The magnificent Hove Mayoral Chain and badge was created by Goldsmiths and Silversmiths Company Ltd., of 112 Regent Street, London at a cost of £300 and was delivered to Hove on 9 December 1899.

It was stated the makers had endeavoured to combine character with the lightness of the later Renaissance. The large badge was a pendant with scrolls enriched with turquoises and pale coral surmounted by Neptune’s trident. The Hove coat of arms was prominently displayed and at one side there was a shield of William I while the other arms related to Queen Victoria’s reign. A Tudor rose and the dates 1066 (first historical mention of Hove) and 1898 (date of incorporation) were also part of the design.

The Mayoress had to wait until 1909 before she too could wear a chain and badge of office. It was of a lighter design and Messrs Lewis & Son of 44/45 King’s Road, Brighton created it. The scrolls on the pendant were enriched with pearls while the centre link from which it hung was of light gold with the device of an anchor and trident on red enamel. The chain was composed of alternate Tudor roses, the letter ‘H’ in blue enamel and pendant-shaped scroll links with red enamel centres. It echoed the Mayoral Chain with Neptune and the two dates already mentioned.

When Brighton and Hove became a unitary authority in 1997, the question arose as to which Mayoral Chain would be used. The Hove one was more beautiful and with more historical worth and was valued at some £82,000 at that time, whereas the Brighton chain and badge were only worth some £50,000 and was never made specifically for the borough, being a second-hand London sheriff’s chain.

Apparently, Brighton councillors baulked at the idea of the new Mayor of Brighton & Hove venturing out bedecked with the Hove Mayoral Chain and Badge and so, regrettably, it is never seen in public.

The Hove Mace

On 16 May 1899 Mortimer Singer of 4 King’s Gardens wrote a letter to Hove Council asking to be allowed the honour and pleasure of presenting the Mace to the Corporation as a mark of my respect for the government of Hove, which has been conspicuous for its excellent work for so many years. Hove Council accepted the offer with alacrity and sent Mr Singer a hearty vote of thanks.

The mace was composed of solid silver, heavily water-gilt, and there was a representation of the imperial crown with orb and cross on the summit. The fillet was set with carbuncles, amethysts and corals and there was enamel work on those parts that would appear above the shoulder and below the hand of the mace-bearer.

Part of the decoration included a symbolic figure of Hove surrounded by figures representing navigation, education, music, industry, steam and electrical progress, science and art. There was also a full blazon of the Hove coat of arms.

The mace was formally presented to the town on 12 October 1899. On 25 January 1900 Hove Council decided to allow five guineas a year plus a uniform to a suitable man to carry out the duties of mace-bearer and the watch committee was to be responsible for finding such a person. The first mace-bearer was Inspector William Fox, aged 45, who had served in Hove Police for 25 years.

Celebrity Speakers, Exhibitions and Shows

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) came to Hove Town Hall on 30 August 1914 to speak in patriotic tones in what was claimed to be one of the earliest, large recruiting drives at the start of the First World War. In fact there was such a crowd of people that they could not all fit in the Town Hall and he was obliged to make a second speech to those still outside.

On 4 July 1921 the great Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton (1874-1922) delivered a lecture to a thrilled audience. Another explorer who made his mark in a different way was Sir Ranulph Fiennes. While he was a student at the Davies Language School he decided to climb the tower of the Town Hall. In November 2013 he said ‘I’m rather fond of Hove. It was the site of my most challenging climb as a student. Hove Town Hall was very difficult, especially in the dark, but we got there in the end.’ He planted a flag on top. It was reported that Hove Fire Brigade were unable to remove the flag because their ladder could not reach that far.

In January 1936 the famous Grey Owl arrived to give a lecture in Hove Town Hall clad in full Native American dress and you could buy tickets for the event from Combridges, the well-known bookseller and stationer’s at 56 Church Road, Hove. It later transpired that Grey Owl, while looking remarkably authentic, had in fact started life as Archie Belaney and was born in Hastings, Sussex. But he was also a passionate conservationist, long before such a concept became mainstream.

John Cowper Powys (1872-1964) was a poet, essayist and novelist. Although he is now highly regarded, he was practically an unknown entity when he gave his first public lecture at Hove Town Hall on the subject of English Literature. His audience consisted of three women and one child.

On 3 June 2013 Nigel Farage, flamboyant leader of UKIP, arrived at Hove Town Hall to address a packed Great Hall of over 400 people. The meeting had been well publicised and a large group of protesters, waving banners and shouting abuse waited outside with two or three police vehicles in the offing. But some of the people they shouted at as they entered the Town Hall were public-spirited citizens attending a blood donor session that was taking place at the same time. Farage had to be spirited inside by a different route and the meeting started late. As soon as he took the microphone, hecklers at the back started shouting ‘racists’ and ‘scum’ and making such a racket that nobody could hear Farage. This happened a few times until all the hecklers had been ejected. Meanwhile, other members of the audience became fed up and shouted ‘what about free speech?’ Eventually, order was restored and Farage, despite looking hot and bothered, was able to present his party’s case. Farage later commented that the meeting had been his roughest ride in England although he had endured some abuse in Edinburgh the previous month, which necessitated him taking refuge in a nearby pub.

Monday - Home Sweet Home

Tuesday - The Blue Bells of Scotland

Wednesday - The Harp That Once in Tara’s Hall

Thursday - March of the Men of Harlech

Friday - The Anchor is Weighed

Saturday - Rule Britannia

Barrel Number Two

Sunday - Sicilian Mariners’ Hymn

Monday - God Bless the Prince of Wales

Tuesday - There’s Nae Luck Aboot the House

Wednesday - The Last Rose of Summer

Thursday - Auld Lang Syne

Friday - Tom Bowling

Saturday - God Save the Queen/King

A somewhat sad anecdote appeared in the Brighton Herald (24 September 1910);

Reference has often been made to the irony of the Hove Town Hall carillons. Another instance occurred last Monday. The magistrates were engaged with a particularly sordid and painful case of parental neglect, when the bells over their heads went sardonically through the strains of Home Sweet Home.

There was an ivory keyboard attached to the carillon apparatus that enabled different tunes to be played on the bells on special occasions. But it was a challenge for a professional organist because it required a different technique and of course there was only a range of twelve notes to strike the twelve bells. The operator had to strike the key sharply with the thumb of a clenched fist.

On 16 July 1893 Mr Crapps played the carillon bells on the occasion of the royal wedding when Prince George, Duke of York (later King George V) married Princess Mary of Teck.

Later on S.H. Baker held the unusual and honorary appointment of Borough Organist of Hove and he played the carillon bells on three historic occasions. They were Armistice Day 1918, Coronation Day 12 May 1937 and V.E. Day 1945. Apparently the keyboard was mislaid between the two first events but fortunately it was discovered and fitted up in time. According to E.V. Lucas the Admiralty stopped the carillons being played during the First World War on the grounds the sound might act as a guide to submarines or aircraft. On VJ Day 1946 the bells started to ring out at 8a.m. with There’s Always Be An England.

In January 1916 it was suggested that the times the carillons played should be altered. Up until then the carillons had been merrily ringing out every three hours from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. The new times restricted their use to four times daily instead. On occasions the carillons could be heard while a concert took place inside the Town Hall, which was a cause of annoyance to some of the audience. By the time the 1950s arrived the carillons only played once a day at 1 p.m.

In 1921 an inspection revealed that sea air had corroded the wires connected to the bells. Messrs Gillett & Johnston recommended phosphor bronze connections should be substituted at a cost of £54. But Hove Council chose the cheaper option of galvanized iron wire with extra heavy ‘S’ hook joints for £48-10s.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton In this view of Church Road looking east towards Hove Town Hall, it is interesting to note Forfars on the left and the Albion on the right, still in existence today. |

Town Hall Clock

Messrs Gillett & Bland supplied the clock at the same time as the carillons at a cost of £1,576-10s. Messrs Salviati, Burke and Company supplied the mosaic clock dials for £180. In December 1892 the surveyor was instructed to fix small gong bells to the winding gear of the clock and carillon to prevent over-winding.

In 1893 when the Hove Commissioners were thinking about installing electricity in the Town Hall, Frank King, consulting electrician, advised against illuminating the clock tower and clock faces because of the ‘amount of experiment in consequence of the novelty of the work’. The surveyor H.H. Scott added the information that owing to the construction of the dial plates, the clock could not be illuminated from the inside.

Eighteen years later technology had improved enough for the illumination to become possible and in March 1911 it was reported that James Warnes Howlett would pay the cost of £300 to have it installed. Alfred Waterhouse’s son drew up the plans and Messrs Gillett & Johnson undertook the work.

Mr G.F. Matthew of the Indian Service (retired) in a letter dated 21 December 1906, complained about the ‘sonorous and penetrating’ chimes of the Town Hall clock; he found the midnight chimes particularly annoying. He asked that the striking mechanism should be stopped between the hours of midnight and 6 a.m. Moreover, sixty-two residents of neighbouring streets added their signatures to the letter. When the committee learned that it would cost £25 to alter the mechanism they decided, after some discussion, that they could not recommend the council to stop the striking at night.

Town Hall Organ

The original organ was a relatively simple instrument. In February 1896 the Town Hall Committee reported they had made enquiries and it would cost from £1,600 to £1,700 to complete the organ in a suitable manner.

By September 1896 the Local Government Board had sanctioned Hove Council’s application to borrow £1,700 to be repaid within a period not exceeding thirty years. In November 1896 Henry Willis of Rotunda Works, Camden Road, London, signed a contract to complete the organ. However, his specification came to more than the original estimate because he stated the work, including mechanical blowing, would cost £1,820.

Henry Willis (1821-1901) was a famous organ builder and he had constructed the organ in the Albert Hall in 1871. He also built the organ in Windsor Castle and others for various halls and cathedrals. In 1885 Henry Willis received a gold medal for his organ building because of the ‘excellence of tone, ingenuity of design and perfection of execution’. The Hove Town Hall had four complete manuals. Henry Willis recommended the pitch for the organ should be the French Diaspon Normal. It is not clear whether or not this was done and altered later but it is a fact the Council Minutes for June 1915 record the pitch should be altered to French Diaspon Normal.

There was also the matter of the water supply to sort out because the great organ was to be blown by three Ross water engines. To operate efficiently these engines needed a constant minimum pressure of 50lbs per square inch whereas in March 1897 the ordinary pressure in the water main at the Town Hall was 35lbs per square inch. An additional connection to the water main by which a minimum pressure of 64lbs could be maintained at all times solved the problem.

On 30 June 1897 Mr H.F. Balfour ceremoniously inaugurated the magnificent newly completed organ. He gave two recitals that day, one starting at 3 p.m. and the other at 8 p.m. He began his performance with Bach’s Tocatta and Fugue in C Major and finished with a stirring rendition of Rossini’s William Tell.

The organ was insured for the sum of £2,000 and ordinary residents of Hove were allowed to use it, provided they could produce a certificate from a qualified organist that they were competent to play. For the serious musician, it was a bargain to be able to play such a fine instrument for 4/- an hour (if you were a Hove resident) or 5/- (if you came from elsewhere). In September 1897 it was decided to install an electric light in the organ loft at a cost of 3/-.

In December 1897 the surveyor H.H. Scott reported that there were sixty-two exposed pipes in the organ front, and they varied in length from 3 feet 6 inches to 13 feet 5 inches, and in diameter from 2 inches to 6 ½ inches. There was a considerable amount of ornamental woodwork in the organ case but the councillors must have thought the pipes looked somewhat bare because they instructed Mr Scott to put some simple decoration on the pipes at a cost of around £40.

In November 1898 the firm of Henry Willis & Son offered Hove Council a special deal for tuning the organ at a cost of £20 a year. They agreed to visit the organ for tuning purposes six times a year, provided that the experienced tuner and his assistants made four of these visits during the course of their ordinary rounds. Otherwise, the cost of hiring two men (including their time, railway, railway, bus or cab fares and hotel expenses) would amount to three guineas for the first day, £4-14-6d for two days and £5-16-6d for a three-day visit. Hove Council sensibly decided to opt for the £20 annual fee.

In the autumn of 1898 Mr Butcher gave four free organ recitals and programmes were not allowed to cost more than one penny.

In May 1928 there were several applications for the post of Honorary Borough Organist. Samuel H. Baker of 14 Wilbury Avenue was chosen for the post. He had been organist and choirmaster at St Mary’s Church, Brighton, and he was formerly deputy organist of Chichester Cathedral. Mr Baker was much in demand for official and semi-official occasions.

Although the organ had once been very popular, by the 1950s it was virtually a forgotten masterpiece. There had not been a single booking for an organ recital during the course of twenty-nine years. When discussing its future, one councillor was of the opinion that ‘organ recitals are as dead as a dodo’. Eventually it was decided to sell the Willis organ to Haberdashers’ Aske’s School at Elstree for the bargain price of £1,500.

Many music buffs were upset at Hove losing such a fine instrument but at least they had the consolation of later knowing that had it remained at Hove, it would have been destroyed with the rest of the Grand Hall in the fire of 1966.

|

| copyright © Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove West side of Hove Town Hall in 1910 |

Sir Charles Aubrey Smith

In May 1889 the Hove Commissioners granted a theatrical licence to the Great Hall and Banqueting Room. Orchestral concerts had already taken place on the stage and in 1887 the Green Room Club for aspiring actors was formed. It seemed the existing stage was not large enough and in 1895 Parsons & Sons were commissioned to erect a moveable timber stage to place in front of the existing platform for the sum of £57-15s.

|

| copyright © Sussex Cricket Museum Sir Charles Aubrey Smith |

It is interesting to note that Sir Charles Aubrey Smith (1863-1948) and his two sisters were keen members of the Green Room Club and rehearsals took place at 56 Norton Road. Their father was a surgeon who lived for many years at 2 Medina Villas but later the family moved to 19 Albany Villas, which was where a commemorative plaque was unveiled in May 1987. Aubrey Smith made his acting debut at Hove Town Hall on 8 November 1888 as Mr McAlister in a production of Ours. His last stage appearance at Hove was also at Hove Town Hall on 17 February 1894. He made his London debut on 9 March 1895 at the Garrick Theatre where he portrayed the clergyman in The Notorious Mrs Ebbsmith.

In 1915 Aubey Smith embarked on his film career; he played the part of Wellington in Queen Victoria. Other notable films he appeared in were Lives of the Bengal Lancers (1935) with Gary Cooper, The Prisoner of Zenda (1937) with Ronald Colman, Madeleine Carroll and Douglas Fairbanks, The Four Feathers (1939) with Ralph Richardson and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1941) with a star-studded cast including Spencer Tracy, Ingrid Bergman and Lana Turner.

As well as being a famous thespian, Aubrey Smith was also a noted all-round sportsman, having gained his blue at Cambridge in 1882. He was a commanding figure with a height of over six feet and he was known as both a batsman and a bowler. From 1882 to 1886 he played cricket for the Sussex team from time to time and was captain from 1887 to 1889. In 1889 at the Sussex County Cricket Ground at Hove, he made 142 for Sussex against Hampshire and in 1890 he took seven wickets for sixteen runs against the MCC at Lords. He earned the nickname of ‘Round the Corner Smith’ because of his angled run-up to the crease. Sometimes he began from a deep mid-off position, while at other times he appeared from behind the umpire. Even the redoubtable W.G. Grace admitted ‘It is rather startling when he suddenly appears at the bowling crease.’ When Aubrey Smith moved to Hollywood and lived in a house in Mulholland Drive, Beverly Hills, he founded the Hollywood Cricket Team, which became a magnet for other British actors in Hollywood such as David Niven, Boris Karloff and Leslie Howard.

Aubrey Smith was also keen on football, playing for such famous teams as the Old Carthusians and Corinthians. In 1944 he was knighted and four years later he died at the age of 85 in Beverly Hills. His ashes were brought back to England and laid in the churchyard of St Leonard’s, Aldrington to join his sisters in the south-west corner.

In November 1898 approval was given for electric footlights to be placed on the stage at a cost of £21 and the orchestra was also to have the benefit of electric lights at a cost of £35. In 1901 it was decided to have electric top lights on the moveable stage instead of gas, which would also reduce the risk of fire. Thus three battens, each carrying twenty electric lamps, were installed at a cost of £50. Another modern innovation was the telephone, already installed in the basement. In September 1894 it was decided to provide a ‘silence box’ for it. Mr Miles was to provide and fix the same for £9-15s.

The Town Hall as a Cinema

While most people acknowledge that the first film show at Hove took place at the Town Hall, there is still some debate as to which film it was and the precise date. Some say the honour belongs to James Williamson who put on a cinematograph and Rontgen Rays show on 16 November 1897.

Others claim the first film shown was George Albert Smith’s Passenger Train made in 1897 and showing the arrival and departure of passengers at Hove Railway Station. (Incidentally, this film and other films made by local pioneers, can be viewed at a special gallery at Hove Museum. Hove is proud of its record in the forefront of the film industry, long before anyone had heard of Hollywood).

The Revd A.D. Spong of the Cliftonville Congregational Church had the bright idea that Passenger Train might amuse the young people of his church – he had already seen a preview. His son, A. Noel Spong, stood at the door collecting ticket money from excited youngsters.

In 1904 Hove Council produced a list of rules to be followed when a cinematograph lantern was in use and fire buckets and a damp blanket were to be placed close at hand. H.H. Scott, borough surveyor, also recommended that a compartment measuring at least six or seven feet should be provided to house the apparatus; it should be lined throughout with sheet iron and have a ventilated top. There was a natural concern about the possibility of fire because the celluloid film in use at the time was highly inflammable. In 1897 there had been the tragic case in Paris when a film show was given at a charity event and the celluloid film caught fire. The resulting blaze caused the death of 121 people.

The rules adopted in January 1904 were as follows;

The lantern must be constructed of metal or lined with metal and asbestos.

A metal shutter, in addition to the revolving disc shutter, must be provided between the source of light and the film, and kept closed except when the film is in motion for the purpose of projection.

If the film does not wind upon a reel or spool immediately after passing through the machine, a metal receptacle with a slot in the metal lid, must be provided for receiving it.

If electric lights are used, the installation must be in accordance with the usual rules, that is the choking coils and switch must be securely fixed on incombustible bases, preferably on a brick wall, and double pole safety fuses must be fitted.

If any oxy-hydrogen gas is used, storage must be in metal cylinders only.

The use of ether or other spirit saturator is not to be permitted under any circumstances.

In 1907 people in other parts of the Town Hall experienced fluctuations in the quality of the electric light whenever there was a film being shown. This was because the system was not designed for such high use and the demand sometimes rose to 60 amperes. In January 1908 Hove Council authorised alterations to the wiring; Page & Miles undertook the work at the modest cost of around £15.

It seems Hove Council were forward-thinking in their safety concerns because it was not until 1 January 1910 that the Cinematograph Act 1909 came into force. All the same some changes had to be made to comply with the new regulations; around £20 was spent on alterations to the operator’s enclosure and a further £24 was expended on providing electrically lit ‘Exit’ signs above each of the eight doors.

Film shows continued to be held at the Town Hall into the 1920s and a particular highlight in January 1920 was a film of the Prince of Wales’s overseas tour. G.H. Whitcomb played stirring music on the Town Hall organ to accompany the flickering film. At first of course Hove Town Hall was the only place where ordinary folk could see a film but soon dedicated cinemas were opened at Hove. The Empire Picture Theatre opened in Haddington Street in 1910, the Hove Electric Empire in George Street opened in 1911 and the Hove Cinema Theatre at 1 Western Road opened in 1912. These cinemas were of modest size and it was not until the early 1930s that large cinemas such as the Granada in Portland Road and the Odeon in Denmark Villas were in business.

Donations to the Town Hall

Gifts to the Town Hall were not unusual. In 1897 Charles H. Nevill of 3 Victoria Mansions offered a marble figure of a seated nymph called Sabrina executed by Holme Cardwell. The Town Hall committee accepted the offer and Sabrina became an adornment to the Mayor’s Parlour. Perhaps the mayor found the figure distracting; at any rate when the new Hove Library opened in 1909, Sabrina was moved there.

In April 1918 Sir George Donaldson (1845-1925) offered to present Hove with another marble statue. It was a 10-foot high replica of Canova’s fine sculpture called the Dancing Girl. Sir George ensured that the statue would be on public display and not tucked away somewhere; he insisted on choosing the spot himself.

Sir George Donaldson was an interesting character and he lived in some splendour at 1 Grand Avenue, Hove. He was an astute art connoisseur, dealer and collector and over the course of thirty years built up a unique range of musical instruments because he was a great music lover with the violin being his favourite instrument. In 1894 he presented this collection to the Royal College of Music. Amongst the treasures was an Italian 15th century upright spinet said to be the oldest keyboard instrument in existence, a pair of ivory and ebony mandolins belonging to the last Doge of Venice and a tortoiseshell guitar on which David Rizzio played before Mary, Queen of Scots. In 1900 he presented a collection of furniture to the Victoria and Albert Museum. Sir George was once heard to comment that Brighton and Hove had no equal in Europe and it was a mark of his respect for Hove that he offered the marble statue.

Hove councillors were moved to expend £50 to construct a special alcove opposite the main entrance to Hove Town Hall to accommodate the Dancing Girl. She stood on a circular pedestal, poised for movement, arms akimbo and wearing a loose, classical garment pinned at the shoulder. The profile of her head revealed her straight Greek nose and her hair was dressed in a ponytail style and adorned with a wreath of flowers. The original sculpture was created in 1805 for the Empress Josephine.

|

| Councillor A.B.S. Fraser Mayor of Hove in 1907 from the 1907 Brighton Season Magazine |

The statue presided over many interesting comings and goings during the course of years. But in January 1966 fire broke out at the Town Hall and although the Dancing Girl survived intact, she was blackened by smoke. Perhaps Hove councillors had more important things to worry about in the wake of the fire and having to find somewhere else for council meetings. At any rate nobody seemed to have much concern for Sir George’s bequest and Anthony Rea purchased her. She was cleaned up and stood for many years outside 3 Adelaide Crescent, adding a touch of elegance to her classic surroundings. Then in February 1995 thieves tried to steal the statue but only succeeded in snapping off her head and arms.

In 1907 Edwin Compton of 87 Goldstone Villas donated a painting by Jules Lessore. It was a view painted in 1882 of the King’s Road and it had cost £150. The painting in its gilt frame was 8-foot wide and hung in the Banqueting Room.

In November 1909 Councillor A.B.S. Fraser, Mayor of Hove, presented an etching by P. Laguillermie from the painting by Edwin Abbey The Coronation of King Edward VIII.

Lady Boyle, who was a member of the Sassoon family, bequeathed a portrait of Edward VII painted by a Mr Berthier. In July 1964 there was a row over a decision to hang this portrait in a corridor on the first floor. Councillor Edward Johnson objected and commented somewhat sourly that he did not like the idea of the council giving priority to ‘pictures of royal personages by artistic nonentities’. Perhaps he had forgotten that Edward VII made several visits to the Sassoons at their Hove home on the seafront and that at the time most residents felt honoured by the association.

|

| copyright © J.Middleton The reading of the proclamation of King George V on the steps of Hove Town Hall 9 May 1910 |

The Hove Mayoral Chain and Badge

The magnificent Hove Mayoral Chain and badge was created by Goldsmiths and Silversmiths Company Ltd., of 112 Regent Street, London at a cost of £300 and was delivered to Hove on 9 December 1899.

Alderman Barnett Marks,

Mayor of Hove in 1911

displaying the mayoral chain and badge.

from the 1912 Brighton Season Magazine

|

It was stated the makers had endeavoured to combine character with the lightness of the later Renaissance. The large badge was a pendant with scrolls enriched with turquoises and pale coral surmounted by Neptune’s trident. The Hove coat of arms was prominently displayed and at one side there was a shield of William I while the other arms related to Queen Victoria’s reign. A Tudor rose and the dates 1066 (first historical mention of Hove) and 1898 (date of incorporation) were also part of the design.

The Mayoress had to wait until 1909 before she too could wear a chain and badge of office. It was of a lighter design and Messrs Lewis & Son of 44/45 King’s Road, Brighton created it. The scrolls on the pendant were enriched with pearls while the centre link from which it hung was of light gold with the device of an anchor and trident on red enamel. The chain was composed of alternate Tudor roses, the letter ‘H’ in blue enamel and pendant-shaped scroll links with red enamel centres. It echoed the Mayoral Chain with Neptune and the two dates already mentioned.

When Brighton and Hove became a unitary authority in 1997, the question arose as to which Mayoral Chain would be used. The Hove one was more beautiful and with more historical worth and was valued at some £82,000 at that time, whereas the Brighton chain and badge were only worth some £50,000 and was never made specifically for the borough, being a second-hand London sheriff’s chain.

Apparently, Brighton councillors baulked at the idea of the new Mayor of Brighton & Hove venturing out bedecked with the Hove Mayoral Chain and Badge and so, regrettably, it is never seen in public.

The Hove Mace

On 16 May 1899 Mortimer Singer of 4 King’s Gardens wrote a letter to Hove Council asking to be allowed the honour and pleasure of presenting the Mace to the Corporation as a mark of my respect for the government of Hove, which has been conspicuous for its excellent work for so many years. Hove Council accepted the offer with alacrity and sent Mr Singer a hearty vote of thanks.

The mace was composed of solid silver, heavily water-gilt, and there was a representation of the imperial crown with orb and cross on the summit. The fillet was set with carbuncles, amethysts and corals and there was enamel work on those parts that would appear above the shoulder and below the hand of the mace-bearer.

Part of the decoration included a symbolic figure of Hove surrounded by figures representing navigation, education, music, industry, steam and electrical progress, science and art. There was also a full blazon of the Hove coat of arms.

The mace was formally presented to the town on 12 October 1899. On 25 January 1900 Hove Council decided to allow five guineas a year plus a uniform to a suitable man to carry out the duties of mace-bearer and the watch committee was to be responsible for finding such a person. The first mace-bearer was Inspector William Fox, aged 45, who had served in Hove Police for 25 years.

Celebrity Speakers, Exhibitions and Shows

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) came to Hove Town Hall on 30 August 1914 to speak in patriotic tones in what was claimed to be one of the earliest, large recruiting drives at the start of the First World War. In fact there was such a crowd of people that they could not all fit in the Town Hall and he was obliged to make a second speech to those still outside.

On 4 July 1921 the great Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton (1874-1922) delivered a lecture to a thrilled audience. Another explorer who made his mark in a different way was Sir Ranulph Fiennes. While he was a student at the Davies Language School he decided to climb the tower of the Town Hall. In November 2013 he said ‘I’m rather fond of Hove. It was the site of my most challenging climb as a student. Hove Town Hall was very difficult, especially in the dark, but we got there in the end.’ He planted a flag on top. It was reported that Hove Fire Brigade were unable to remove the flag because their ladder could not reach that far.

In January 1936 the famous Grey Owl arrived to give a lecture in Hove Town Hall clad in full Native American dress and you could buy tickets for the event from Combridges, the well-known bookseller and stationer’s at 56 Church Road, Hove. It later transpired that Grey Owl, while looking remarkably authentic, had in fact started life as Archie Belaney and was born in Hastings, Sussex. But he was also a passionate conservationist, long before such a concept became mainstream.

John Cowper Powys (1872-1964) was a poet, essayist and novelist. Although he is now highly regarded, he was practically an unknown entity when he gave his first public lecture at Hove Town Hall on the subject of English Literature. His audience consisted of three women and one child.

On 3 June 2013 Nigel Farage, flamboyant leader of UKIP, arrived at Hove Town Hall to address a packed Great Hall of over 400 people. The meeting had been well publicised and a large group of protesters, waving banners and shouting abuse waited outside with two or three police vehicles in the offing. But some of the people they shouted at as they entered the Town Hall were public-spirited citizens attending a blood donor session that was taking place at the same time. Farage had to be spirited inside by a different route and the meeting started late. As soon as he took the microphone, hecklers at the back started shouting ‘racists’ and ‘scum’ and making such a racket that nobody could hear Farage. This happened a few times until all the hecklers had been ejected. Meanwhile, other members of the audience became fed up and shouted ‘what about free speech?’ Eventually, order was restored and Farage, despite looking hot and bothered, was able to present his party’s case. Farage later commented that the meeting had been his roughest ride in England although he had endured some abuse in Edinburgh the previous month, which necessitated him taking refuge in a nearby pub.

***

On 4 January 1888 a Plain and Fancy Dress Ball was held at Hove Town Hall with the proceeds going to the institution later called Hove Hospital. The Gaekwar of Baroda was one of the guests and at the time he was staying for a couple of months at Adelaide Crescent. During his visit, he went to Mr Hawkins’s photographic establishment in King’s Road, Brighton where he sat for his portrait wearing native dress and decorations including the Star of India. A selection of these portraits were despatched to Queen Victoria. His family were famous for their marvellous collection of jewels. In 1886 the Gaekwar had sent a Pigeon House to be exhibited at the Indian & Colonial Exhibition in London. It stood some twenty feet high and was a mass of intricate cravings depicting birds, animals and flowers. By coincidence or design the Baroda Pigeon House was given to Hove in 1926 and stood in the grounds of Hove Museum. Unhappily, it was allowed to deteriorate to such an extent that it was removed in 1959 and presumably destroyed. On a happier note the Jaipur Gateway, which also arrived at Hove in 1926 and was exhibited in the same exhibition too, has fared better and has been carefully restored.

In October 1927 Mrs Woodhouse organised a Loan Exhibition of Antique Embroideries at the Town Hall. It was a prestigious event and Mrs Woodhouse was assisted in the enterprise by Lady Ada Boyd, Lady Violet Crawley, Lady Algernon Gordon Lennox, the Hon. Lady Keppel and Lady Mary Ward. The Queen, as patron, sent a set of baby clothes once worn by George IV, Sir Philip Sassoon loaned a number of needlework carpets and hangings while the Duke of Portland sent a curious picture worked in feathers. The Duke of Devonshire loaned a series of late 14th century panels, the Duke of Northumberland sent an embroidered claret velvet suit with a white satin waistcoat while the Earl of Mount Edgcumbe provided an altar frontal dating from the time of Henry VIII. Altogether there were 300 exhibits.

It will be obvious from the foregoing paragraph that Mrs Woodhouse was very well connected indeed. Her husband was Major Robert Woodhouse who served in the Boer War with the Essex Yeomanry. He was taken prisoner and sent to a concentration camp where he found there were no surgical instruments available. But he was a skilled ironworker and he set about creating serviceable surgical instruments out of any pieces of iron or fragments of metal he could find. Major Woodhouse was also a goldsmith and silversmith and possessed his own hallmark. In their home at 9 Wilbury Avenue, Hove, he had his own forge and he made some miniature items for the Queen’s Doll’s House, including a tiny gold punch bowl complete with cups and ladles. He made all his family’s wedding rings and rings for the royal family too. Queen Mary was a good friend who used to visit them at Hove. As these were strictly private visits, they were not always reported in the Press but Queen Mary was known to have visited on 5 April 1929. When Major Woodhouse died aged 82 on 4 December 1936, the Queen telephoned personally with a message of sympathy. The Woodhouse’s only son Captain Cecil Woodhouse was killed in the First World War and their grandson the 4th Marquis of Dufferin and Ava was killed in Burma in the Second World War.

On 27 April 1938 the Y.M.C.A. held a fund-raising bazaar at the Town Hall and Sir Malcolm Campbell (1885-1949) arrived to open it. He started racing motor-cycles in 1906, took up flying in 1909 and embarked on his motor racing career in 1910. In 1938 it was stated he could travel at 300 miles per hour.

In October 1927 Mrs Woodhouse organised a Loan Exhibition of Antique Embroideries at the Town Hall. It was a prestigious event and Mrs Woodhouse was assisted in the enterprise by Lady Ada Boyd, Lady Violet Crawley, Lady Algernon Gordon Lennox, the Hon. Lady Keppel and Lady Mary Ward. The Queen, as patron, sent a set of baby clothes once worn by George IV, Sir Philip Sassoon loaned a number of needlework carpets and hangings while the Duke of Portland sent a curious picture worked in feathers. The Duke of Devonshire loaned a series of late 14th century panels, the Duke of Northumberland sent an embroidered claret velvet suit with a white satin waistcoat while the Earl of Mount Edgcumbe provided an altar frontal dating from the time of Henry VIII. Altogether there were 300 exhibits.

It will be obvious from the foregoing paragraph that Mrs Woodhouse was very well connected indeed. Her husband was Major Robert Woodhouse who served in the Boer War with the Essex Yeomanry. He was taken prisoner and sent to a concentration camp where he found there were no surgical instruments available. But he was a skilled ironworker and he set about creating serviceable surgical instruments out of any pieces of iron or fragments of metal he could find. Major Woodhouse was also a goldsmith and silversmith and possessed his own hallmark. In their home at 9 Wilbury Avenue, Hove, he had his own forge and he made some miniature items for the Queen’s Doll’s House, including a tiny gold punch bowl complete with cups and ladles. He made all his family’s wedding rings and rings for the royal family too. Queen Mary was a good friend who used to visit them at Hove. As these were strictly private visits, they were not always reported in the Press but Queen Mary was known to have visited on 5 April 1929. When Major Woodhouse died aged 82 on 4 December 1936, the Queen telephoned personally with a message of sympathy. The Woodhouse’s only son Captain Cecil Woodhouse was killed in the First World War and their grandson the 4th Marquis of Dufferin and Ava was killed in Burma in the Second World War.

|

| copyright © Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove From the Herald collection. Showing an image of Girls Life Brigade at Hove Town Hall. 12 February, 1938. |

On 27 April 1938 the Y.M.C.A. held a fund-raising bazaar at the Town Hall and Sir Malcolm Campbell (1885-1949) arrived to open it. He started racing motor-cycles in 1906, took up flying in 1909 and embarked on his motor racing career in 1910. In 1938 it was stated he could travel at 300 miles per hour.

Visit of the First Battle Squadron

In July 1914 the First Battle Squadron of the British Fleet visited Hove and were given a warm welcome by the populace. Officers and men were treated royally and given a special dinner at Hove Town Hall at tables prettily decorated with flowers. The kitchen must have been busy because beef, veal and ham plus roast haunches and ribs of Southdown lamb were provided, followed by fruit tarts, custard tarts and hot plum puddings; there was ale and lemonade to drink. During the repast the band of the Queen’s Regiment provided a musical accompaniment. Afterwards, all the men were presented with packets of cigarettes and inscribed memento tobacco boxes.

First World War

|

| copyright © Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove A Red Cross fund raising event at Hove Town Hall in 1916 |

During the early part of the First World War, the Great Hall was used for Sunday ‘At Homes’ because there was nowhere for the soldiers to go; sometimes there would be as many as 500 visitors. Tea and refreshments were provided and the current newspapers were laid out; the men could also play chess and draughts and there was entertainment such as singing and instrumental music.

In December 1914 permission was given to the 2nd (Hove) Battalion Home Protection Brigade to use the Great Hall for drill purposes during bad weather (if lettings permitted) provided that the men did not wear ‘nail boots’.

Second World War

On 22 September 1939 the Supreme War Council met in a committee room adjoining the Council Chamber. The British representatives were Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax and the Minister for Co-ordination and Defence Lord Chatfield. The French representatives had flown into Shoreham Airport especially for the meeting and were the Premier M. Daladier, the Minister of Armaments M. Dautry, the Commander-in-Chief of the French Armed Forces General Gamelin, and the Chief of Naval Staff Admiral Darlan. Later they adjourned for lunch at the Prince’s Hotel on the south-east corner of Grand Avenue.

On the subject of food, there was a British Restaurant at the Town Hall during the war years that offered a meal for a reasonable price and the service continued until 31 March 1946. Food was always in short supply and so use had to be made of whatever was available. In June 1946 the Old Folks’ Dinner included stewed rabbit and rabbit pie.

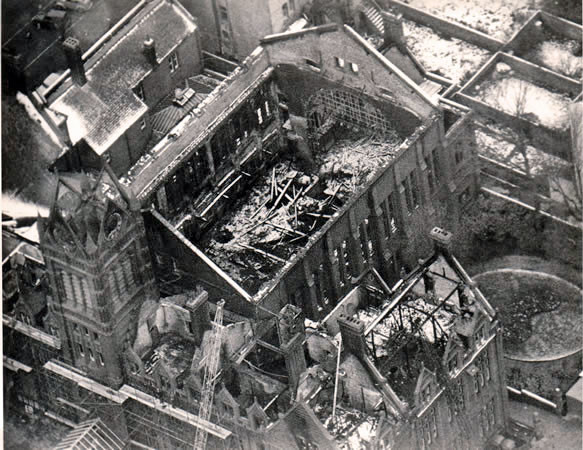

Town Hall Fire

Jimmy Fergusson, a Metropole Casino steward, was the first person to notice the fire at 3.14 a.m. on Sunday 9 January 1966. Hove Fire Brigade received the information at 3.15 a.m. and two minutes later the brigade phoned for more appliances to join them; Brighton Fire Brigade and Shoreham Fire Brigade were soon on their way. By 3.30 a.m. a further radio request for back-up was made and men and appliances from Hastings, Seaford, Newhaven, Lewes, Keymer, Haywards Heath, Horsham and Worthing rushed to Hove.

Eventually, there were at the scene some seventy firemen busily using twelve pumps, three turntable ladders, twelve hand jets and two turntable ladders with fixed jets. Mr W. Holland, Chief Fire Officer of East Sussex, together with his deputy, directed operations.

Already at 3.17 a.m. the fire had a strong hold on the Great Hall, the Banqueting Room and Council Chamber and flames rose up through three stories to the roof at the south west corner. Until 3.30 a.m. nobody knew there were six people trapped in the top-floor flat at the south west corner. They were Stanley Burtenshaw, Town Hall Keeper, his wife and their children, 19-year old Gordon and 15-year old Alison, plus the Burtenshaw’s friends Mr and Mrs Ashdown. These people were all brought down to the ground by ladder and the rescue operation was complete by 3. 45 a.m. They were taken to Hove Hospital but only Mr Burtenshaw was detained because he had been overcome by smoke inhalation.

At that time firemen still hoped to save the clock tower but the way was blocked by intense heat and suddenly the tower roof went up in a flash, scattering burning embers far and wide. The firemen managed to get out just in time before the clock weights and winding machinery came crashing down. The bells fell too but only as far as the steel joists fixed some five years previously when the cradle holding the bells was found to be weak.

Four courageous firemen saved the west side of the Town Hall by going up to the burning roof through a hatch and extinguishing the fire from there. By 6 a.m. the fire-fighters were able to radio back that they had the fire surrounded. Curiously enough, while all this was going on, there was one window-box where the yellow wall-flowers remained unblemished.

John Barter, secretary to the Mayor of Hove, made a brave dash into the Town Hall in order to save the Hove mace and the Mayor and Mayoress’s regalia from destruction. As Jean Garratt remarked afterwards, perhaps the prayer uttered by the Revd T. Peachey at the opening in 1882 still held good; he thanked God that the building had been completed ‘without hurt or harm to any engaged upon it’. The last civic function held at the Town Hall was the Mayor and Mayoress’s Christmas Eve cocktail party when a group of young girls sang carols by candlelight.

It was the worst fire in Hove’s history and ironically steps had already been taken to improve fire precautions at the Town Hall with some £7,000 set aside. The fire was believed to have originated in a dustbin in the catering area. Once the fire had a hold, there was plenty of pitch-pine, wooden panelling, and foam rubber in the seating to fuel it, plus a ventilation system with a great deal of concealed ducting; there were no fire doors and no automatic fire alarm.

When dawn broke, the scene was devastating – a roofless and gutted Town Hall with only the western portion intact. Even so the Town Hall could have been rebuilt behind the walls still standing, if there had been the will to undertake such a task. Unhappily, the 1960s was a low point in the appreciation of Victorian architecture. For many years people who were knowledgeable about architecture, including the noted historian Antony Dale, were inclined to view Waterhouse’s structure as a red-brick monstrosity.

But for those of us who remember the warm tones of brick and terracotta and lovely décor of the old Town Hall, with daffodils in the window boxes in the spring set against a blue sky, its passing can only be a matter of great regret. There was also the sad demise of the carillon bells that provided such a unique charm to central Hove; the workers in the vicinity knew lunchtime had arrived when the bells began to ring.

At first it seemed the carillons might be saved an a report in the Brighton Herald (28 January 1966) said the cracked bells were resting in the corporation yard and would be recast, including Big Tom, weighing 2 ½ tons. But after much discussion the decision was taken to demolish the Town Hall completely and start again from scratch.

In October 1971 the Town Hall was handed over to contractors Walter Llewellyn & Sons to be demolished. The western section housing the magistrate’s court and court offices were kept in operation until the new Law Courts were completed in Holland Road in August 1971. Demolition work began on 13 October 1971 and the last part to fall on 11 November 1971 was the magistrate’s court.

The New Hove Town Hall