Judy Middleton 2003 (revised 2023)

|

copyright © J.Middleton

St Helen’s Church is bathed in sunshine in this photograph

taken on 18 July 2010. |

St Helen

The church was named after St Helena (c.255-c.330) mother of

Constantine the Great. In A.D. 292 Constantine’s army in York proclaimed him

Emperor and he gave his mother the title of Dowager Empress. This must have

mitigated the humiliation suffered by St Helena of having been divorced by the

Emperor Constantius Chlorus for no other reason than it was politically

expedient to do so.

There is an old tradition that St Helena was born in Britain

and might have been the daughter of the British king of Colchester, Coel. This

may explain why she was chosen to be patron of the little church at Hangleton.

Other sources claim a more humble origin, namely that she was the daughter of

an innkeeper in Bithynia.

St Helena is supposed to have travelled to Jerusalem where

she discovered the true cross, buried near the site of Calvary. She is also

credited with founding the basilica on the Mount of Olives as well as the

basilica at Bethlehem.

Architecture

|

copyright © J.Middleton

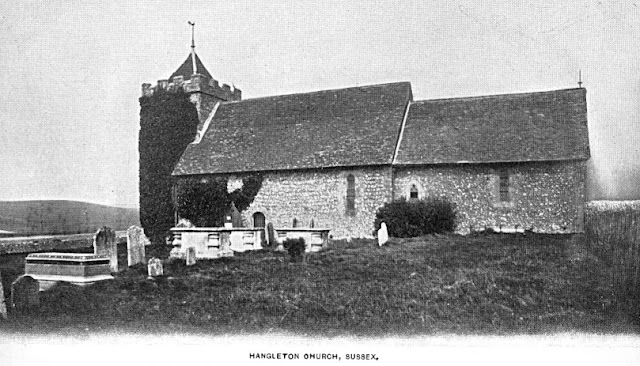

This old coloured postcard view shows the tower of St Helen

swamped with ivy. |

St Helen’s Church was probably built in the late 11th

century although some experts consider it might have originated in earlier

times. Similar to many Downland churches, it was built of flint with Caen stone

used for quoins, door and window dressings.

In the south wall flints were laid diagonally and then in

reverse direction in a pattern known as herringbone. This style was favoured by

Saxon builders and led the author Barr-Hamilton in his book Saxon Sussex to

conclude that St Helen’s was one of the best examples of Saxon herringboning.

Other authorities are not so convinced; for example, E.A. Fisher in Saxon

Churches of Sussex prefers to leave the question open as to whether St

Helen’s had Saxon or Norman origins. Colin Laker is of the opinion that

herringbone work was ‘a common feature of Norman churches’.

St Helen’s was built as a simple rectangle with a length of

62 feet and a width of 17 ½ feet; the walls being an impressive three-foot

thick.

The brick-paved floor slopes upwards from the west towards

the chancel;

St Nicolas Church, Portslade, and St Margaret’s Church,

Rottingdean, also share this characteristic. Another feature that St Nicolas

and St Helen have in common is a low-side window. There is still some debate

about the purpose of a low-side window. A popular theory was that it enabled a

leper to observe Mass being said without entering the church. More prosaically,

a low-side window might have been fitted with a hinged shutter that could be opened and a bell rung to summon the

faithful. Perhaps it was used for confessions, with the priest hidden from view

inside the church and the penitent outside.

The roof has a steep pitch indicating that the original roof

was thatched. The roof was re-constructed in the 13th century

although some of the original timbers might have been retained.

|

copyright © D.Sharp

There

are three carved objects on the south facing tower, a head in the centre, which could

represent one of the various people connected to the Church, such as the Prior

of St Pancras who may have financed the tower's building, a stonemason or the parish priest,

below the head is a shield shape carving which could be a spade or an upturned

stonemason’s mallet, to the left and above the head is an indeterminate creature’s

head. |

In around 1300 a tower was erected at the west end while a

new chancel was built at the east, the old Norman one being destroyed. The

chancel windows with their trefoil heads thus date from this time. The present

chancel roof was constructed in around 1700.

It seems that there were once four windows, two on either

side of the nave. For some reason during the re-construction work of around

1300 they were blocked up. It was not until 1969 that two of the windows were

unblocked, revealing early painted decoration that had been preserved by the

blocking-up. The other two windows were left concealed.

Another feature that

remained hidden until modern times was the north door. It was discovered when a

new vestry was being built.

St Helen's Church is the oldest surviving building in the City of Brighton & Hove.

Wall Paintings

It is interesting to note that there were three different

periods of mediaeval wall paintings at St. Helen’s. There were also wall

paintings at

St Nicolas, Portslade. It is tempting to speculate that the same

hands were responsible for the decoration in both churches. Unhappily, in the

latter case the wall paintings are deemed to have been lost forever because of

successive coats of lime-wash.

But at St Helen’s traces have been retrieved successfully.

The earliest style dates back to the 13th century with scroll-work

worked in red with some yellow lines.

|

copyright © D.Sharp

The 15th century figure of St Christopher in reddish garments can be see at the left of the photograph |

|

copyright © D.Sharp

The 17th century

rear quarters of

a lion |

A tall figure of St Christopher was painted on the north

wall in the 15

th century; his staff rested on top of the window that

had been filled-in by then. Black was used to depict the grass while the

riverbank was brown. St Christopher was a popular saint of the period and was

nearly always painted on the wall facing the main entrance. People believed

that by looking upon his image, they would be saved from harm or sudden death

that day. An extension of this idea exists to this day when many people like to

have a St Christopher medallion about their person to protect them in their

travels.

On the west of the north wall there was a painting dating

from about the 17th century. All that was visible was the rear quarters of

a lion and so it was presumed to have formed part of a royal coat of arms.

In 1521 the Pope granted Henry VIII the title of ‘Defender of the Faith’, Royal Coats of Arms of the King or Queen of the day were painted on some church walls or hung in the form of painted boards or plaques. It would remind a congregation in a visual way, that after the split with Rome, the monarch was the head of the Church and not the Pope. St Helen’s royal coat of arms would have probably been painted over in the time of Oliver Cromwell when the link between Royalty and the Church was broken. At the time of the English Civil War 1642-1651, Hangleton was in the part of Sussex that supported the Parliamentarians.

|

copyright © D.Sharp

The south doorway of St Helen's |

A Scratch Dial

The Sussex Archeological Collection reported in 1962 that

there is a scratch dial situated on the top stone of the

east jamb of the south door. It is a very worn specimen and mounted upside down

and is one of sixteen scratch dials in East Sussex.

Scratch dials were a primitive form of a sun-dial; they

worked on the same principle whereby a gnomen cast a shadow over the face, not

intended to tell the time but to indicated the time of Mass and in most cases

Vespers.

It is interesting to note that scratch dials are also to be

found on some of the older churches in Normandy.

By the end of the 15th century clocks had come into use and so scratch dials were no longer of importance.

Richard Bellingham

|

copyright © D.Sharp

The monument depicts Richard

Bellington and his wife Mary at their devotions, kneeling at a prie-dieu with a book open

on either side. A line of small sons stretches behind Richard; they are Edward,

Richard, Henry, John and Timothy. Five daughters knelt behind Mary; they are

Mary, Jane, Dorothy, Margaret and ?. |

In the south east corner of the chancel there is an

interesting monument that Colin Laker identified as belonging to Richard

Bellingham who died at

Hangleton Manor in 1597. The monument depicts Richard

and his wife Mary at their devotions, kneeling at a prie-dieu with a book open

on either side. A line of small sons stretches behind Richard; they are Edward,

Richard, Henry, John and Timothy. Five daughters knelt behind Mary; they are

Mary, Jane, Dorothy, Margaret and an unknown daughter's name. Nine children might seem an enormous family

to present day sensibilities but the Bellinghams had five more who died in

infancy. They are not forgotten either and four daughters and one son are

represented wearing their christening robes (to signify death in infancy) below

where Richard and Mary kneel.

Charles Clayton writing in 1885, suggested the long speech ribbons 'would have had the customary ‘Jesu Mercy’, but these have been sadly obliterated over time by accident or design'. The word ‘Mercy’ is just discernable today from Richard

Bellingham's speech ribbon.

There was once a similar monument in St Peter’s Church,

Preston to the memory of Anthony Shirley, his wife Barbara and their children.

The couple also knelt at their prayer desks while their seven sons and five

daughters were shown grouped below them. The boys were identified by their

Christian names. This monument remained extant until the early 19th

century.

Ann Norton

The earliest ledger stone set in the floor of the aisle

belongs to Ann Norton who died in 1749; she was the daughter of John Norton of

Portslade and his wife Ann. Perhaps she was also a relative of Revd Robert

Norton who was rector of Hangleton from 1755 to 1757.

Font

There used to be a font made of lead dated 1717 inside the

church; it remained until at least 1865.

Church Bell

Mears & Co of London cast the bell in 1863.

Sir George Cokayne

|

copyright © J.Middleton

The bleakness of the spot occupied by St Helen’s at the head

of a windswept valley is emphasised in this photograph. |

|

copyright © J.Middleton

This map was drawn from the 1870 Ordnance Survey 6 inch map

and shows the position of St Helen's, the lost medieval village

and Hangleton Manor. |

St Helen’s Church was fortunate in escaping the attention of

zealous Victorian restorers and thus it retains more of the appearance of a

mediaeval church that other old churches in the Hove and Portslade area.

Although Hangleton had once been a prosperous parish with

people earning their living by growing crops and keeping sheep on Downland

pastures, the ravages of the Black Death in 1348 and 1349 led to a dramatic

decline in population; by 1428 there were just two households in the entire

parish.

Charles Clayton writing in 1885 reported “The Sexton tells me that he

finds it quite impossible to dig in any part of

St Helen's churchyard (not a

very small one) without disturbing previous interments, and the whole

ground is full of bones up to the top, This hardly seems accounted for

by an average population of Hangleton of 30 or 40 souls. It may

possibly be that the Black Death (1348-9) or some similar pestilence

nearly exterminated the parish, but no reference appears to show this."

An official report of 1724 stated that there were only five

families living in the parish. The largest family were Quakers and therefore

had no interest in the parish church. The altar stood against the wall but

there was no rail in front of it as there should have been. But then no service

of Holy Communion had been celebrated there within living memory.

On 30 March 1851 a Religious Census was undertaken. At St

Helen’s it was recorded that there were 95 seats in the church and 25 of them

were free. On Sunday morning there were fourteen souls in attendance and not

surprisingly there was no service in the afternoon. The value of the tithes was

put at £299.

By the late 19th century St Helen’s was in a poor

state with the tower open to the sky. It could have been left to quietly

moulder away were it not for the intervention of Sir George Cokayne, Clarenceux

King of Arms. It was he who in 1870 paid for the church and roof to be repaired

and thus saved it for future generations.

Stained Glass Windows

|

copyright © D.Sharp

left:- St Helena, centre:- Thou art the King of Glory. O Christ (Tu rex gloriae Christe),

lower centre:- angel holding an image of first Easter morning, right:- St Nicolas |

|

copyright © D.Sharp

The Great War

memorial window |

The three-light window has been altered twice, once in 1876

and again in 1910 when the present stained glass was inserted. St Helena is

depicted in the left-hand light, crowned and holding a cross while St Nicolas

occupies the right-hand light. The risen Christ is the theme of the upper part

of the central light and a small angel kneels below holding a framed picture of

the first Easter morning.

W. Bainbridge Reynolds designed and executed the glass and

Walter Tapper, architect to York Minister, was responsible for the tracery and

stonework.

The window was in memory of Sophia Courtney Boyle and it was

stated that ‘330 sorrowing friends’ subscribed to the cost. Miss Boyle died on

14 June 1908 and she was the sister of

Revd Vicars Armstrong Boyle, vicar of St

Nicolas Church, Portslade and rector of St Helen’s Church, Hangleton. According

to the memorial tablet at St Nicolas ‘she was his constant companion and fellow

worker, brave, intelligent, faithful, simple, generous’. The Bishop of Lewes

dedicated the window on 26 March 1910.

The stained glass lancet in the north wall was given in

memory of men who died in the Great War.

Reredos, Screen and Panelling

In 1925 widowed Mrs Nevett donated the reredos, screen and

panelling in memory of her late husband William Nevett. A plaque with these

details was placed on the west side of the chancel.

|

copyright © D.Sharp

The 1925 reredos, screen and

panelling, on the north wall of the sanctury is the William Willet stone Pietá

|

|

copyright © D.Sharp

Henry Willett (1823-1905) |

On the same side there is a delightful stone Pietá; it was

given as a memorial to Henry Willett (1823-1905) a successful Brighton brewer

who amassed an extensive collection of English pottery that he later gave to

Brighton Museum and it still has pride of place.

It is perhaps a strange

coincidence that one of the pieces is of the celebrated Dr Kenealy who lies

buried in St Helen’s churchyard.

Edward Kenealy QC., an Irish born Barrister and writer lived at 163 Wellington Road, Portslade, with his wife and eleven children from the 1850s until the mid 1870s. Kenealy commuted to London and Oxford for his law practice but returned at weekends to be with his family. He chose Portslade because of his love of the sea, of which he wrote,

"Oh, how I am delighted with this sea-scenery and with my little marine hut ! The musical waves, the ethereal atmosphere, all make me feel as in the olden golden days when I was a boy and dreamed of Heaven".

While living in Portslade he wrote the greater portion of his unorthodox theological works. He came to national prominence in 1874 when he acted as leading counsel for the "Tichborne Claimant", which became one of the most notorious 19th century trials in British legal history, leading to Kenealy being disbarred from his profession.

In 1875 Edward Kenealy was elected MP for Stoke which he held until the 1880 General Election. He died later that same year.

It is a mystery as to why Dr Kenealy was buried in

St Helen’s churchyard. He lived in what was then the separate Parish of

St Andrews Portslade which did not have a churchyard although

Portslade Cemetery was available. If he had insisted on a church burial, the only option available would have been St Helen’s in the united Parishes of Portslade & Hangleton as

St Nicolas churchyard had been closed for burials since 1872 .

|

copyright © D.Sharp

Edward Vaughan Kenealy's marble tomb in St Helen's churchyard |

Documented History

An early mention of the church occurs in 1093 when William

de Warenne donated St Helen’s along with five other churches to the great

Cluniac Priory of St Pancras at Lewes.

St Helen’s also gains a mention when Siffrid II, Bishop of

Chichester (1180-1204) granted a charter to the Priory of St Pancras.

In 1386 Thomas Rushoke, Bishop of Chichester, excommunicated

Nicholas Sprot, rector of Hangleton. His offence is not known and although

excommunication was a serious punishment, the fact that many other clerics were

in the same boat suggests it was likely to have been a dispute about tithes or

clerical subsidies. Revd Nicholas Sprot was rector from 1380 to 1403 and so

whatever the circumstances, he managed to keep his benefice.

In 1634 John Bridge, Parson of Hangleton and Vicar of Portslade, donated 10 shillings for the rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral London, (22 years later the medieval St Paul’s Cathedral was completely destroyed in the 1666 Great Fire of London, 10 shillings would pay a craftsman’s wages for two weeks)

Early Bequests

Some early bequests to St Helen’s Church were as follows:

Richard Scrase wrote his will on 25 February 1486/7 and left

3/4d for the maintenance of the high altar, and 5/- for general repairs.

Another Richard Scrase wrote his will 21 February 1499/1500.

It seems he neglected to pay his dues towards the church and it must have

bothered his conscience because he left 5/- to the high altar ‘for tithes

forgotten’; he also bequeathed 6/8d to the church.

In 1516/17 John Sommer of Portslade left the church a

quarter of barley.

In 1550 Richard Bellingham of Newtimber left five marks for

church repairs while 6/8d was to be put in the poor box.

Revd Henry Boner, vicar of Patcham, wrote his will on 17

March 1551/2 leaving ‘my grett sylver spone’ (sic) to Sir Henry Hornbye, parson

of Hangleton.

Advowson

The advowson (patronage) of St Helen’s Church originally

belonged to the Prior of St Pancras, Lewes, until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1537.

From

1537 until his excecution in 1540 Thomas

Cromwell, Earl of Essex was the patron.

In 1541 the Crown granted the

patronage of St Helen’s to the former Queen, Anne of Cleves for her lifetime. When Anne died in 1557 the patronage passed to the Bellingham

family.

Mary Whitstone inherited it from Edward Bellingham. But in

1599 Mary died and the advowson reverted to Thomas Sackville, Lord Buckhurst,

who had purchased Hangleton Manor and property two years previously.

On 22 October 1785 John Frederick, Duke of Dorset, sold some

property to his trustees, including the advowson of Hangleton church together

with the tithes.

In 1815 Revd Henry Hoper became vicar of Portslade and

rector of Hangleton. It was Charles, Lord Viscount Whitworth, and Arabella,

Duchess of Dorset who presented him to the benefice of Hangleton.

Defence of the Realm

It may be an amusing footnote to us, but at one time clergy

were expected to provide towards the cost of defending the realm. For example,

in 1612 the Roll of Armor (sic) stipulated that Mr Boone of Hangleton

and Glynde (he enjoyed a double benefice) must provide a ‘musquet furnished’.

Non-attendance

In 1674 the churchwardens of St Helen reported to the

authorities that Arthur Hoader had not attended church and moreover he had not

receive the Sacrament at Easter.

Register Troubles

A fascinating but mutilated note survives to this day dated

16 June 1679. It states ‘At ye Request of my Neighbour Tutt … to let you know

yet we have neither Reg(ister) …belonging to the parish church of Hangleton …

had any Marriages, Christ’nings or Burials … there of severall yeares last

past’. (sic)

Revd John Temple wrote the above note and it was addressed to a Mr Jones.

|

copyright © J.Middleton

It was the same Revd John Temple who recorded the following event in the

Portslade Parish Register:

‘By the Sacred Providence of Almighty God the old

Church Register of Portslade was burnt by lightening together with ye Parsonage

House of Hangleton on 31 May 1666’.

Ironically, it was in the same year as the

Great Fire of London. |

More is known about Revd John Temple than any other of the

early priests at Hangleton. He was inducted as rector in 1660 and became vicar

of Portslade on 26 June 1669. His wife Elizabeth was buried on 27 March 1683.

But confusingly his second wife must have been called Elizabeth too because the

birth was recorded on 24 April 1707 of Elizabeth Courtney, daughter of John

Temple and Elizabeth. Temple became a property owner at Portslade and this

included a rood of land known as The Weare. On 24 May 1705 there was a poll for

the knights of the shire at Lewes and at Portslade there were just five voters,

with Temple being one of them; Temple voted for Sir Henry Peachey and the

Honourable H. Lumley. By 1707 Temple had retired and a new priest had taken

over his priestly duties. Temple was buried on 12 February 1708 and his widow

did not wait even six months before she re-married. Her bridegroom was Revd

Lewis Beaumont, rector of Pyecombe, and the marriage took place on 25 July

1708. Mrs Beaumont sold The Weare to Revd John Tattersall, the next incumbent

at Portslade.

In 1954 when excavations were being made prior to building

the present church hall, some remains of the old parsonage came to light, thus

adding weight to Temple’s testimony. The old parsonage was situated to the

north east of the church.

A remote Downland Church

|

copyright © Brighton &

Hove City Libraries

An Edwardian view of St Helen's in a remote and rural setting |

It is difficult to realise now quite how open the landscape was before the late 1930s house building boom, which went on continuously through to the 1960s.

Arthur George Holl, writing in 1897 said,

‘everyone who has

journeyed by the

Dyke Railway will have noticed a short distance after

leaving the main Portsmouth line and to their left hand side a sacred

edifice (St Helen’s Church) standing absolutely alone, open to all the elements which pass

over these wind swept Downs'.

|

copyright

© Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Brighton

Herald 14 June 1913

These airman were well of course to crash near St Helen’s Church,

which is 4 miles to the east of Shoreham Aerodrome, possibly they

completely missed a visual sighting of the River Adur which flows past

the aerodrome and flew over the Downs too far to the east to have

crashed in Hangleton. |

Ongoing Repairs

St Helen’s was repaired again in 1929. But the beams

remained hidden behind coats of plaster and thus nobody could see what sort of

condition they were in. The quandary was resolved some years later when a chunk

of plaster fell down and a close inspection revealed the presence of

death-watch beetle. Indeed, so serious was the situation that the church had to

be closed temporarily because the roof was deemed unsafe.

The new roof cost around £2,500, a considerable sum in those

days when it was possible to buy a house for that amount. Some ancient timber

was used for the beams that came from an old property being demolished around

this time. St Helen’s re-opened in 1949.

However, repairs were by no means complete and during some

severe winter weather, snow descended upon the altar and choir stalls. At last

by 1951 the restoration was finished and moreover there was electric light and

heating, a great boon in the winter. Lady Dance made the latter possible by

providing the funds.

United Parishes

|

copyright © D.Sharp

St

Nicolas Church c.1170, is less than 2 miles from Hangleton and a very similar architectural design to St Helen’s with almost identical windows placements, St Nicolas has a much larger tower and nave floor area. |

Hangleton had a long history of being run in harness with

another parish. In the 1550s Henry Hornby was the priest of Hangleton as well

as being vicar of

St Nicolas Portslade.

|

copyright © J.Middleton

St Helen's Church

|

On 9 June 1585 Archbishop Whitgift (the see of Chichester

being vacant) united the benefices of Hangleton and Blatchington.

In 1590 Revd Richard Mann had the living at Newtimber as

well as at Hangleton.

In 1612 Hangleton was in the care of Mr Boone who was also

vicar of Glynde. Revd John Bridge followed him and he was also vicar of

Portslade.

Revd John Temple was in charge of Portslade and Hangleton

from the 1660s.

On the 28 July 1864 Hangleton and Portslade were formally united under Order of Council.

Revd Richard Enraght who lived in

Station Road was Curate-in-Charge of St Andrews Portslade with St Helen's Hangleton from 1871 to 1874. Fr. Enraght’s belief in the Church of England's Catholic Tradition, his promotion of ritualism in worship, and his writings on Catholic Worship and Church-State relationships, led him into conflict with the Disraeli Government's Public Worship Regulation Act, for which he paid the maximum penalty under the Law, of prosecution, imprisonment and eviction with his young family from the Holy Trinity Church vicarage in Birmingham in 1880. He became nationally and internationally known as a "prisoner for conscience sake".

When Revd R.C. Desch was inducted in 1946, the Bishop of

Chichester said he intended to separate the parishes of Portslade and

Hangleton. But the legal and financial position proved difficult while the

Ecclesiastical Commissioners refused to sanction the separation of the parishes

until Hangleton had a much larger population. Legally, the Bishop could not

make Hangleton a conventional district but he did appoint a priest-in-charge. It

was complicated because legally the vicar of Portslade was still officially

rector of Hangleton. Although he derived 60% of his income from its endowments

he had no control or responsibility for the welfare of the parish.

In 1955 St Helen's had its first Parish Priest appointed for over 400 years when the Parish of Hangleton was formally separated from the Parish of Portslade by Order of Council on the 15 April 1955.

Revd Peter Bide

The first Parish Priest in 1955, was a Fr Peter Bide, previously a curate at St Nicolas Portslade for six years. Fr Bide was a close family friend of the writer C.S. Lewis from their college days.

At Oxford in 1957 Joy Davidman, whom C. S. Lewis deeply loved and had married a year earlier in a civil ceremony, was coming to the end of her life with cancer. C. S. Lewis had never acknowledged that his own civil marriage was in fact a valid marriage at all, as it was only used as an act of expediency to prevent Joy Davidman, an American divorcee, from being deported. With Joy’s health now becoming critical, C.S. Lewis asked his friend Fr Bide to visit him at Oxford. Lewis had heard that Fr Bide had once healed a suffering parishioner, and wanted him to anoint Joy. After the Service of Extreme Unction (Service for the Dying), Lewis immediately ask Fr Bide to marry them as it was Joy’s dying wish to be married in a church. Lewis had previously asked several Oxford college chaplains to do this, but all had felt inhibited by the Bishop of Oxford’s decree that the church’s prohibition of re-marriage for divorcees should be upheld in his diocese.

Fr. Bide carefully considered the request and, since he was not under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Oxford, went ahead and administered the Sacraments of Holy Matrimony and Holy Communion in the hospital ward the following day.

Fr Bide later reflected: "I had no jurisdiction in the Diocese of Oxford. The example of my fellow priests showed that I should be guilty of a grave breach of Church law. I asked Jack (C. S. Lewis) to leave me alone for a while and I considered the matter. In the end there seemed only one Court of Appeal. I asked myself what He would have done - and that somehow finished the argument..."

After the Service of Extreme Unction and the marriage the following day, Joy Davidman made an apparently miraculous recovery. The cancer went into remission, although it returned in 1959. She and Lewis had three years of idyllic happiness until her death in July 1960. C.S. Lewis died three years later on the 22nd November 1963. The reporting of the death of one of the greatest Christian writers of the 20th century was over-shadowed by world events, as this was the same day that President Kennedy was assassinated.

The Bishop of Oxford was furious and severely reprimanded Fr Bide for performing the marriage ceremony, and reported the matter to the Bishop of Chichester, George Bell, who gently rebuked Fr Bide and immediately removed him from his living at Hangleton.

Bishop Bell followed this action by appointing Fr Bide as Vicar of the larger Parish of Goring by Sea !

Fr Peter Bide's wife is buried in

St Helen's churchyard.

St

Helen’s Church – List of Incumbents

1278

Richard?

1331/39

John de Motbury

1364/1368

Robert ate Grene

1380

Thomas Cheyning

1380

Nicholas Sprot

1391 Simon Ingolf

1404

William Newton

1407

John Lokyngton

1442

William Worthe

1444

Thomas Whyte

1478 Walter Coye (or Cone)

1485 John Hugh

1511/12

Henry Prior

1523

Henry Horneby (or Hornby) also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1551 Richard Hide, Curate of Portslade with Hangleton

1558

Richard Darrell

1559

John Wilson also Rector of St Leonard's Aldrington

1568/9

Edward Crackell also Rector of West Blatchington, his brother Richard is

buried in St Helen’s churchyard

1582/3

Henry Shales also Rector of West Blatchington

1584

Henry Englisshe also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1585

Thomas Wilshaw also Rector of West Blatchington

1589/90 John Postletwaite also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1590 Richard Man (or Mann) also Rector of Newtimber

1606 Richard Edwards, Curate of Hangleton with Newtimber

1609/10 John Boone (or Bonner) also Rector of Glynde

1613 John Bridge also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1636 John Belgrave

1660

John Temple also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1709

John Tattersall

1740/1

Edward Raynes

1742 John Osborne, Curate of Portslade with Hangleton

1755

Robert Norton also Rector of Southwick (West Sussex)

1757 John Clutton

also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1815

Henry Hoper also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1815 Thomas Scutt, Curate of Portslade with Hangleton

1859

John Peat

1863

Fred. Geo. Holbrooke also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1864, on the 28 July, The Parish of Portslade and the Parish of Hangleton were

formally united under Order of Council

1871-1874

Richard Enraght, Curate-in-Charge of

St Andrews Portslade with Hangleton.

In later years, Fr Enraght became

famous in England and the USA as a 'Prisoner of Conscience'.1872-St Nicolas Schools built in Locks Hill, Portslade, the foundation stone plaque reads - “These Schools were erected by Hannah Brakenbury for the benefit of the Poor of the united Parishes of Portslade and Hangleton A.D. 1872” (see below)

1880

Charles Stevens also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1899 Vicars Armstrong Boyle also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

(buried in St Helen’s churchyard)

1919 Donald Campbell also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1927

Lubin Creasey also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1928

Noel Hemsworth also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1933

Ernest Holmes also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade (buried in St

Helen’s churchyard)

1943

Peter Osborne, Curate of Hangleton and Portslade

1946

Roland Desch also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1948 Ronald

Adams also Vicar of St Nicolas Portslade

1955, on

the 15 April, the Parish of Hangleton was formally separated from the

Parish of Portslade by Order of Council

1955 Peter Bide (former Curate at St Nicolas Portslade)

1955 David Ince, Curate of Hangleton

1957 Max Godden

1963 Edward Taylor

1973 Kenneth Holder

1980 Thomas Inman

1987 John Joyce

1995 Andrew Sage

2000 Keith Perkinton

2021 David Hazell – Priest in Charge

********

Today, the Vicar of Hangleton also has responsibility for St Richard’s Church but at least it is in the same parish.

In Locks Hill, Portslade on the front of the Brackenbury Primary School (the former

St Nicolas CofE Junior School which was re-built next door in the late 1960s and vacated these premises) there is a present day reminder of the once united Parishes of Portslade and Hangleton in the form of a stone plaque which states,

|

copyright © J.Middleton

The school is a present day reminder of the former

united Parishes of Portslade & Hangleton

which was founded for the poor children of the Parishes |

“These Schools were erected by

Hannah Brakenbury for the benefit of the Poor of the united Parishes of Portslade and Hangleton

A.D. 1872”

The plaque states 'schools', meaning boys and girls were educated separately in the same building and the schools were specifically for the children ‘of the labouring,

manufacturing and other poorer classes of the united Parishes. The 'poor' children of Hangleton would have had to walk on unmade roads and dirt tracks, an incredibly long distance by modern standards to get to the Brackenbury Church School in Portslade (which was renamed St Nicolas Church Schools in the 1880s)

Hannah's tomb is in the Brackenbury Chapel in

St Nicolas Church

St Helen's Churchyard on the 'Silver Screen'

James Williamson (1855-1933) was one of the early pioneers of British film making and ran his Williamson Kinematograph Company studios at various locations in Hove until 1902 when he finally located his studios in Cambridge Grove off Wilbury Villas. Williamson's dramas and comedies were sold all across Europe and America. In 1909 Williamson produced the film ‘

The Boy and the Convict’. This 12 minute length silent drama film was a very condensed version of Charles Dickens’

Great Expectations. The scene with the boy at his Mother’s grave and his meeting with the escaped convict was filmed in

St Helen’s churchyard by the west wall.

Windfall Money

In the 1990s St Helen’s received a windfall in the shape of

compensation paid by South Coast Power for the disruption caused by laying a

gas pipeline to the new Southwick Power Station. According to Brighton &

Hove News the money amounted to £10,000 but according to the Argus (29

February 2000) there was a grant of £27,000. But Revd Andrew C. Sage, vicar

of St Helen’s 1995-2004, states that the grant the church received

was actually £25K and some of it was spent on flood-lighting, which

he personally designed. The rest meant that the old flint walls of

the churchyard could at last receive the specialist attention they

deserved. Revd Sage has since become Canon Sage and in 2022 is vicar

of St Stephen on the Cliffs, Blackpool.

While

Revd Sage was still at St Helen’s, he was delighted by the generous

gift of Mrs Mary Bangs, the well-known local artist and keen history

buff, which enabled the precious wall paintings to be consolidated

and exposed for future generations to enjoy. The windows at St

Helen’s were also repaired – both the stained-glass windows and

the plain-leaded ones, but this gift was anonymous.

See also

St Helen's Churchyard

Sources

British Film Insitute

Christine & Phil James

Encyclopaedia of Hove and Portslade

Laker, Colin A Guide to the Parish of Hangleton and its

Churches (1964)

London Gazette

Sussex Archaeological Collections

The Parish of St Helen's & St Richard's Hangleton

The Friends of St. Helen's campaigning group, has been set up to raise awareness of the plight of St. Helen's, which is the oldest surviving building in the City of Brighton & Hove, as there is a very real threat, and a distinct possibility that this beautiful 11th century medieval church may have to close due to dwindling finances, To become a member of the

Friends of St Helen’s only requires a modest membership fee annually, you do not have to live in Hangleton or Sussex or even in the UK to become a member of the

Friends of St Helen’s.

see:-

The Friends of St. Helen's web page for more detailed information.

Copyright © J.Middleton 2017

page

layout and additional research by D.Sharp